-

“It used to be rare that journalists would come here,” says Elton Caushi, head of tour operator Albanian Trip, who I meet in the capital, Tirana. “When they did come, they only wanted to talk about blood feuds and sworn virgins.”

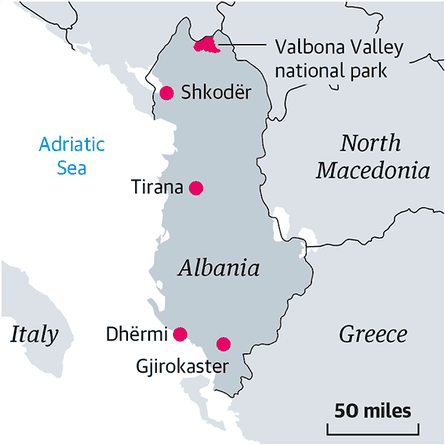

The traditions that once dominated tribal politics in Albania’s mountains are interesting, but I’m here to probe a more recent view of the south-east European country. Thanks to its beaches, Unesco-stamped cities and hiking routes, formerly communist Albania is being lauded as a “hot new” European travel destination beyond backpacking and dark tourism.

For decades, Albania had a reputation as a dangerous, no-go country, thanks largely to its being politically isolated under dictator Enver Hoxha, who died in 1985. After Albania’s 1997 civil war and the end of the Kosovo war in 1999, more visitors gradually started coming to Albania, attracted partly by prices lower than in Greece and Italy. In 2009, 1.9 million tourists travelled to Albania; in 2019, the last full pre-Covid year, the figure was 6.4 million.

The food here may be a factor in this shift. I’m with Caushi in a nameless restaurant at 1001 Bardhok Biba, a street close to the city centre. “The tourists haven’t found it – it’s mainly drivers eating here,” he says. I breakfast on sumptuous tasqebap – a soupy mix of veal, garlic, onions and tomato sauce – before Caushi takes me for 9am dessert at Mon Amour, a Parisian-style patisserie. We pay a non-Parisian 390 lek (£2.80) for coffee and baklava pastries with ice-cream.

After breakfast I drive to Dhërmi, a village that has seen myriad hotels pop up along its coast over the past decade. I arrive at the beginning of Kala, one of many small dance music festivals that have sprung up along the Riviera, with dancefloors on the sand.

The 18th-century Mesi bridge in Shkodër, built by an Ottoman pasha. Dhërmi’s main, non-festival beach is clean, neatly covered in sunbeds and flanked by restaurants. All fine if you just want to lie back and plough through your Kindle. The small beaches north of here, such as Splendor Del Mar and Empire Beach Resort, feel gloriously Balearic in comparison. Swimming in the clear, turquoise sea off Splendor is clock-slowingly tranquil. I haven’t had a better dip outside Asia.

Later, on a walk to nearby Gjipe beach – sandy, lovely, isolated, with zero hotel development – I spot a concrete bunker and stare at this dome with a sea view: a grey lump of cold war paranoia on an otherwise idyllic coast.

I see another bunker. Then another, in the hills when I drive back to Dhërmi. I begin counting them, but soon realise bunkers are as common here as the sunbathing skinks. About 173,371 were reportedly built in Albania between 1975 and 1983, as Hoxha prepared for potential attack.

Caushi warned me that the touristy cities of Durrës and Sarandë were already attracting enough holidaymakers to make them unpleasantly crowded. I stop instead in Gjirokastër and Berat: two smaller cities of renowned beauty.

I prepare by reading Chronicle in Stone, the 1971 novel by Ismail Kadare – Albania’s noted author and Gjirokastër resident. In the book the romance of Gjirokastër’s steep, bumpy paths, snaking around buildings such as Skenduli House and Zekate House – owned by elite families and now museums – shines through his story of 1940s bombardments.

His ink covers the city – my hotel is on Ismael Kadare Street. However, Gjirokastër was once as famous for cannabis as Kadare, according to Blero Topulli, who works in the castle of Gjirokastër. “It was considered one of the most dangerous points in Europe – we had a village producing tonnes of cannabis,” he says. “When I was a child in the 2000s, to see a tourist was like seeing an alien.”

We meet in the castle overlooking the village of Lazarat, which was rife with illegal drug production until a police crackdown in the mid-2010s.

Tirana has a rich cafe culture. Photograph: Andfoto/Alamy Thanks to its historical architecture, Gjirokastër became a Unesco site in 2005, but Topulli says tourists didn’t arrive in significant numbers until the cannabis gangsters had left. We walk the bazaar streets, renovated five years ago for this tourism tilt, but it’s easy to escape this mildly Disneyfied pocket of the city. Topulli takes me uphill to watch the sunset, passing mansions depicted by Edward Lear in the mid-19th century.

“Listen: the wind in the trees sounds like the sea,” says Topolli. He’s right: it laps my ears as the castle’s lights flick on, a calming comedown after Kala’s beach parties.

Further north in Berat, also a Unesco-listed city, I walk up to the castle. Berat has a similar historic richness to Gjirokastër – and similarly steep climbs – but feels more rugged.

The breezy lack of health and safety concerns in Berat makes it even more enjoyable. At the Red Mosque ruins, I scurry up the scarily thin tower’s pitch-black interior, popping my head over the top so vertigo can override my rising claustrophobia.

“I came to Albania because you can do beach, cities and hiking in a week,” a US tourist tells me. Indeed, after a two-hour drive to Tirana it’s a two-hour bus ride to Shkodër, gateway to the Albanian Alps.

I do a classic trek: the 17km route between Valbona and Theth in the Valbona Valley national park. To get in the mood, I read Edith Durham’s High Albania, the British writer’s document of the region’s tribes, based on her 1908 treks. The toughness of the climb, with horse-dotted woods giving way to craggy half-paths, threatens to outmatch the wild beauty of the area. But three hours in I reach the peak, and the forest-splashed views work their magic: it’s Swiss-level stunning.

UK tourists head to Albania for ‘sense of exotic’ without long-haul flight

UK tourists head to Albania for ‘sense of exotic’ without long-haul flightIn mountain-cradled Theth, my guesthouse pancake breakfast is soundtracked by the tense “click-click-click” of diggers. The snaking road to Shkodër was surfaced with asphalt for the first time last year.

Caushi says that some fear Theth’s new highway could lead to overtourism. “But I’m happy for my friends there: 15 years ago you’d see a cow, a chicken, a cornfield. Now they can get to school faster, to the hospital … it’s good for the locals.”

Good for me too, I think, as my bus to Shkodër glides over asphalt.

I finish back in Tirana, staying at Hotel Boutique Kotoni in the city centre, then the quieter Morina hotel, next to the Grand Park of Tirana. Being the capital city of a country with an anti-capitalist regime until 1992, Tirana didn’t get proper bars until well into the 1990s, according to Caushi. After a construction boom in the 2000s, the city now has a population of 560,000. Hoxha’s opulent former residence has a trendy cafe directly in front of it.

I’m in Tirana fleetingly, but visit Bunkart 1, Hoxha’s underground complex, which is now a museum and art space. Exhibitions outline decades of dictatorship, interspersed with art installations. Wrongly balanced, the mix of dark history and video art could come across as distastefully hipster-ish, but it’s captivatingly moving.

Exploring Georgia: Where Ancient Traditions Meet Stunning Landscapes

Georgia is a small country with a big heart, located between Europe and Asia. Known for its rich history, warm...